11/8/2014

|

| Mansion at Bletchley Park |

Baby was so excited this morning—actually, when hasn’t she

been super chirpy this trip? It’s all the places she wants to visit. We’d

watched Bletchley Circle on PBS and really loved all the girl power in

Bletchley. So, Bletchley Park was very high on Angel’s list of places to visit.

The park is operating on winter hours now, so 9:30am to 4pm.

Angel thought that should be plenty of time for us (“We haven’t been in a

single castle for more than 3 hours”). Ha. We ended up staying til they kicked

us out of Block B—well, not really kicked, but they were turning off the lights

as we finished each portion of the exhibit. This happened to us in the Roman

Baths too. We seem to be the last to come out of a lot of things.

Bletchley Park is a 1.5 hour train ride away from

Birmingham. I found out later today that Bletchley is actually closer to London

by ½ hour, so if we ever decide to come back (we totally want to!), we should

do it as a day trip from London.

The walk to BP was very short from the Bletchley train

station. Turn right, cross the street, and you’re there! We entered the main

gate and saw this:

*gasp* Benedict Cumberbatch! As Alan Turing! Angel was

super, super stoked…until we saw the exhibit dates. It doesn’t open until

Monday, November 10th. Argh. We missed it by 2 days! And then Angel

posed the question—what if we come back on Monday? That’s how much she wants to

see the exhibit. She didn’t even mind paying again for the train ride here and

the admission tickets. I had a buy 1, get 1 free voucher to BP from the Days

Out Guide, so I thought why not, we already saved a bit today, let’s come back

on Monday.

As it turns out, when you pay for Bletchley admission, you

get a season ticket that’s valid for a whole year.

So we can totally go again next year…and we’re going on Monday again, to see the Turing exhibit. Angel and Dad are Turing buffs, so I guess we’ll bring Dad along next year.

The head of Britain’s intelligence agency, Admiral Hugh

Sinclair, bought Bletchley Park with his own money during WWII. London was

under heavy bombing from the Germans and he didn’t want his code-breaking

operations jeopardized by bombing, which is why he chose to locate the operations

at Bletchley, a rural country mansion. Bletchley is perfectly located in the

middle of Oxford and Cambridge, the two universities they recruited a lot of

their codebreakers from.

It was crucial that the Germans never learn of Bletchley Park, so they explained away all the people congregating at BP as “Captain Ridley’s hunting party.”

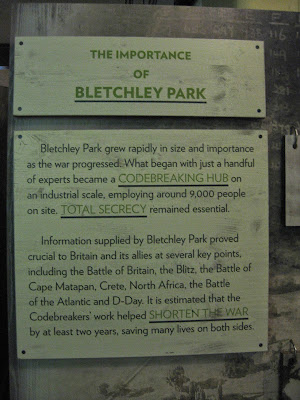

Initially a motley crew of 200 people, BP grew to a force of almost 9000 strong by the end of the war. 2/3 of which were women.

There were linguists, mathematicians, engineers who all came

together to brainstorm, think outside of the box to break German codes.

They first began recruiting debutantes to work here, as they thought that debutantes would keep secrets better. The girls would enter through the gates and be herded up to the mansion, where they were to sign the Official Secrets Act. The commanding officer would instill in them the fear of God should they ever reveal any information to another person of what they were doing at BP. So they never talked about their work even to each other.

When the war was over, all the code-breaking machines were

ordered to be dismantled and all the papers burned. The men and women who

worked here left to return to ordinary citizen lives and they weren’t allowed

to speak of their time at Bletchley, even to their spouses. So many died taking

the secrets of Bletchley to their graves.

General Eisenhower had this to say about the workers at

Bletchley:

Churchill put it most apt, that Bletchley workers were the “geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled.” In the age of Facebook and Twitter, who would be able to do that? It’s crazy that this group of dedicated people kept mum for so long. So long, the general public never learned of Bletchley’s existence until 30 years later!

Perhaps one of Bletchley’s greatest achievements (besides

being the birthplace of the computer age) is that the code-breakers were able

to confirm that Hitler thought the Allies’ invasion would begin at Calais, thus

helping ensure the success of Normandy on 6/6. Double agents had been sent out

to drop clues to German agents that the Allies were planning to do a

preliminary invasion of Normandy as a feint, and that their biggest invasion

efforts would then be at Calais. It was essential to learn if Hitler swallowed

the false information, and at the 11th hour, code-breakers at

Bletchley found out that yes, Hitler believed the double agents’ information.

His decision to move most his forces to Calais to block the

Allies helped turn the tide of WWII. D-Day landings were a success and most

importantly, double agents had led Hitler to believe that an invasion at Calais

was imminent after Normandy…which Hitler believed for more than a month.

Alan Turing, with some of the most brilliant minds in

Britain, worked at Bletchley, trying to come up with ways to break German

codes. In a letter dated October 1941, some of the heads of Bletchley

(including Turing), wrote directly to Churchill, complaining of lack of resources

and funds.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, Churchill believed in the

work they were doing at Bletchley. He remained convinced that breaking the

codes was crucial to winning the war, so he wrote back to Turing and

colleagues:

“Make sure they have all they want extreme priority and

report to me that this has been done.”

|

| Can you read Churchill's writing? I can't! |

Google has donated a lot of money to BP over the years to help restore Bletchley.

There were dispatch motorcycles on display. Most of the

riders were women, who drove all over the country, collecting intercepted radio

traffic from Y centers (Wireless Intercept = ‘WI’ = Y) and delivering it to

Bletchley to be code-broken. The dispatch riders were initially recruited from

amateur riding enthusiasts and they drove their own motorcycles. They’d drive

under any weather condition, be it hail or snow, to get this vital information

to Bletchley in a timely manner. They didn’t know what exactly was in the bags

they were delivering, just that this was part of the war effort and that they

were doing their part to help their country.

German Enigma and Lorenz encoding machines were on display,

as were the British counterpart, the Typex. The Typex was developed using

Enigma as a prototype by the British Air Ministry Signals department. They were

advised that they might be infringing on patents, but the government responded

in typical bureautic fashion that they would consider paying the patent holders

after the war was over. Effectively, this gave them free reign to do whatever

they wanted without paying—if the war was won, the company might not be in

existence any longer (as the company was German). If the war was lost, then

there would be no British government to pay the royalties. How devilishly

clever. In any case, the government later said that to pay the royalties would

mean admitting the Typex was in existence, and as it’s crucial to never let the

existence of Typex be known, then they shouldn’t pay the royalties.

The deciphering machine, the Bombe (well, a recreation

anyway, because the originals had been ordered destroyed so that no other

country would learn that Britain and America knew how to decode the Germans’

code. Even during WWII, Britain and America never let Russia know that they knew

how to decode German code. This would prove vital during the Cold War) was also

on display, built by a group of volunteers in the 2000s.

The Bombe machines were developed by Alan Turing and Gordon

Welchman and were used to test out possible Enigma settings much faster than

humans. This was critical because the Enigma settings were changed on a 24-hour

basis.

After having their code broken with humiliating ease during

WWI, Germany spent a good decade researching ways to create an invincible code.

The government bought encoding machines from the company Lorenz (the machines

were sold on open market so anyone could buy them), and changed them to make

them more secure.

The culture of Nazi Germany was that they were the

invincible race. This spread to their thinking that their code was unbreakable.

And for a time, it was. I was reading how they encoded using the Enigma machine

and my head was spinning from how crazy it was that BP codebreakers even

attempted to make sense of the gibberish the Enigma was spitting out.

Germans were so confident that the Allies wouldn’t be able

to break their code, they transmitted over the radio using Morse code. Of

course, radio’s easy to listen in. England had a lot of centers around the

country with Intercept Operators listening in to the Germans’ gibberish 24/7.

The machine encodes in a way so that there are 158 million,

million, million ways to decode.

That’s crazy! Tiltman made a go at it, and figured out a pattern after 10 days

of continuous work. These brilliant geniuses at BP would work round the clock

at the beginning of the war, and it’s said that they were distracted by the

humdrums of daily life. A women who worked at Bletchley described them as

“unclean,” and they often threw their cups into the lake instead of losing time

(and train of thought) taking the cups back to the canteen. Dilly Knox, another

of Bletchley’s geniuses, was said to do his best thinking during his hours in

the bathtub.

This is the building that housed a lot of the Enigma

codebreaking machines, where the workers worked tirelessly to decode Italian,

Japanese and German codes:

Since most of the buildings were hastily built during WWII,

a lot of the buildings were destroyed after the war.

When Hitler was gaining power in the 1930s and before WWII

broke out, a Polish post office clerk noticed a big package sitting in the post

office that was addressed to German officers. The rather astute postal clerk

and his colleagues opened the package and figured out that this was a new type

of encoding machine. They took meticulous pictures of the machine, then

dismantled it to see how it worked before putting everything back together

again and wrapping it up. The German officers came to pick up the package,

never the wiser that it’d been opened—and dismantled, no less!

The information was given to Polish cryptanalysts, who were

able to use the photographs to build a model of the German encoding machine.

They were able to listen in successfully on German plans for a good few years

before German officers added additional security features.

Then WWII broke out for good. France became occupied,

Britain under air bomb siege. The Polish cryptanalysts called a conference with

the Allies and handed off the blueprints of the German encoding machine. This

was a vital piece of missing information for the Allies. They were able to take

what the Poles had given them and run with it, ultimately producing the Bombe

machine, which could quickly compute and spit out what the day’s key might be.

|

| The Bombe machine |

The Bombe machine was so called because the Polish

cryptanalysts had called their model, the precursor to the Bombe, the “Bomba.” They’d

been eating a particular type of ice cream called the “Bomba” at a café. The

word was corrupted into English, then turned into Bombe.

The Bombes were operated mostly by WRNS (Women’s Royal Navy,

or WRENS).

|

| Enigma machine once owned by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini |

A Japanese flag thought to be worn by a Kamikaze pilot:

He would have worn the flag around his head, like a scarf. The flag is adorned with well-wisher’s good lucks, like “At least I shall kill one enemy for the Emperor.”

They had an exhibit about double agents. Juan Pujol was

codenamed Garbo because he was considered such a good actor, in the league of

Greta Garbo. He was awarded medals by both sides, the British Empire and the

German Iron Cross. 3 hours after the D-Day landings had started, he informed

German intelligence of the fact, and it was the first reporting that German

intelligence got of the D-Day landings that day. This enhanced his reputation

for accuracy. He then convinced German intelligence that the Normandy invasion

was a deception, and the main invasion area would be Calais. Hitler believed

him and 12 German armored divisions remained at Calais for 120 days. Even after

the blows at D-Day, Hitler didn’t move these divisions.

Another agent convinced German intelligence to open up a spy

outpost because he claimed he could successfully recruit spies abroad. He was

given funding for this, and he set up fake spies to claim their paychecks. The

money was funneled into MI5, some 85,000 pounds.

As Alan Turing worked here as one of the first codebreakers

at Bletchley, they had a lot of information detailing his life. Sadly, not many

of his personal effects remain. A cherished watch was on display, as was his

teddy bear, Porgy. He bought Porgy when he was an adult:

At Cambridge, he would practice his lectures in front of

Porgy. Ha. It’s like I always tell Angel…talk to the wall! Well, I tell her to

talk to Pooh too, but she’d rather flap his arms around at me.

Turing was a rower on the Cambridge rowing team as well as a

cross country runner. Very accomplished man! After his death, his mother lived

to research his works and achievements, but his time at Bletchley was still

state secret. It was only some years after his death that she received a letter

that detailed a wee bit of her son’s accomplishments at Bletchley. She made the

connection to his letters during those years as “His enforced silence

concerning his work quite ruined him as a correspondent; his letters from then

on became infrequent and scrappy.”

One of Turing’s most important papers (posing the question

“Can machines think?”) was on display.

There’s a guided tour every ½ hour starting at noon, with

the last one at 2:30pm. You have to go up to the mansion to get a ticket to the

tour (included in price of admission). All the tickets to the 1:30pm were

taken, so we had to wait for the 2pm tour. It was pouring rain by that time and

freezing cold. The tour starts at the Chauffeur’s Hut, then takes you along the

grounds to point out key aspects. Like the stables, where there’s a pigeon loft

above the stables. Technology was advancing rapidly in WWII, but they still

relied on messenger pigeons to relay messages. The pigeons were considered a

reliable way to get information into the necessary hands.

|

| Stable with pigeon loft above |

This is the gate the recruited girls would travel through

when they first arrived at Bletchley:

Also the cottages where the senior code-breakers assembled,

like Dilly Knox of the long baths and Alan Turing:

Angel: After an entire day at Bletchley with countless

interactive exhibits explaining the workings of the Enigma and Lorenz machines,

Jen wanted to have a section about the “things that turn” on the blog. =)

The Enigma was used by the rest of the German army and each unit

had their own “menu” that reset at midnight every day. The navy had a different

Enigma machine from the army which had 4 rotators instead of only 3, making the

naval encryptions harder to crack.

To prevent the enemy from finding out that the Enigma code

had been cracked, reports from Bletchley were often reworded to make it appear

that the information had come from spies working abroad.

There was a different cipher machine known as the Lorenz

which was reserved for Hitler and his highest generals to use; it was in theory

more cryptographically secure and was codenamed “Fish” by the people at

Bletchley Park. However, in the end its code was still broken in part due to a

German operator’s error of sending a long message (around 4000 characters)

twice using the same wheel-combination. This gave the code-breakers at

Bletchley the needed depth to crack the code.

The Lorenz was only declassified in 2003, so a lot of people

who worked on decoding it had already died.

When we arrived back in Birmingham, it was to find this:

A full-on Christmas parade was in progress and it cut off

the main road! We had no way of getting across to get to our hotel, except to

walk all the way down the street to where the parade had already ended, cross

there, and come back around again. I wanted to watch the parade, as there were

a lot of people on both sides watching with excitement. Angel said, “You think

they’ve never seen a Disney parade before, and Disney parades are better.” :P

No comments:

Post a Comment