11/10/2014

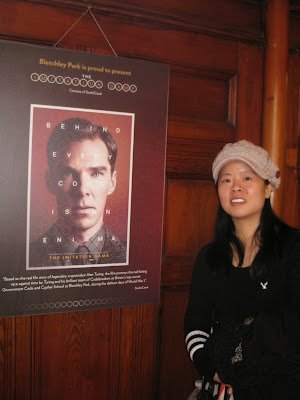

We went back to Bletchley today, as one day is really just

not enough to explore all the exhibits. Also, today was the opening day to The

Imitation Game exhibit at Bletchley. We were the first visitors ever to the

exhibit! That’s pretty thrilling (yeah, dorky I know). Mainly because when

Bletchley opened this morning, we were the first people inside…and it’s a

Monday, so not a lot of tourists in this neck of the woods.

These outfits and the props were actually used in the movie!

|

| Benedict Cumberbatch’s outfit (portraying Alan Turing) |

The desk and outfit worn by Charles Dance (aka the Head Lannister, according to Baby), portraying Commander Denniston:

Baby with her idol…Tywin Lannister, the general who stays behind the front lines.

Angel: Tywin came to the front lines at the Battle of

Blackwater! Mua!

Jen: He only came to the front lines once he knew his side

would win. He arrived just in time to slaughter Stannis’s army.

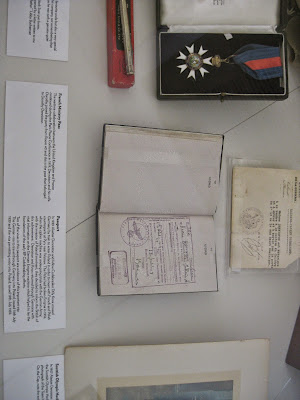

The identification card of Alan Turing, portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch:

|

| The “Ultra” stamp of Commander Denniston’s |

The identification card of Alan Turing, portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch:

The filmmakers reproduced a lot of documents based on

archives of Bletchley Park. They reproduced the crosswords that were used as a

successful recruiting tool during the war. The heads of Bletchley couldn’t

advertise that they were recruiting people as that would give away the ultra

secrecy that Bletchley even existed. At first, they tried to ask different

government departments to allocate admin staff to Bletchley, but most departments

needed their admin staff so that was a no-go. Bletchley was really hurting for

people, so they recruited using the old boys’ network, going to Oxford and

Cambridge where the most brilliant young minds were at during the day, and

recruiting debutantes because they thought debutantes were more likely to keep

secrets.

Since they couldn’t advertise recruiting, they would send

letters to potential “candidates” (who had no idea what Bletchley was). The

letter would merely say that if you wanted to do your part for the government

(which everyone wanted to do during the war), please attend an interview. One

of the tests used was crossword puzzles, and Joan Clarke (played by Keira

Knightley) completed hers in under six minutes. Wowza.

I think I’d figure out 3 of the words before I gave up.

Always hated crossword puzzles. Angel brightened up though, because she’s

always loved doing crossword puzzles. I remember her doing them every morning

during breakfast when we were in high school…I don’t think I knew any person

besides her who would spend time on those things.

We went to the National Computing Museum adjacent to

Bletchley in the afternoon (more on that later), and the tour guide said that

The Imitation Game took a lot of creative liberties with the facts. He said the

movie was all in “good fun,” but not to take The Imitation Game as a history

lesson. Hehe good tip, as I tend to believe just about everything people tell me.

So when the filmmakers said that they tried to recreate everything as authentic

as possible—down to the documents—I guess they’re talking about set design?

|

| Alan Turing’s desk in the movie |

|

| the bar used in the set design is located in Bletchley’s ballroom |

The Bombe machine (recreated by movie set production):

It was here that we first read about the tragic chain of

events that led to Alan Turing’s suicide. Outside a cinema, Turing met a young

19-year-old man and asked him to lunch. A few days later, Turing’s house was

burglarized and he called the police to report the burglary. When the police

interviewed Turing, he admitted to having sexual relations with another man,

which was a major no-no in those days. It was illegal. So, he was tried for

indecent behavior (Regina vs. Turing—“Regina,” we learned, is the Latin word

for “The Crown.” Kinda like in the US, where it’d be State vs. whoever. If it’s

the king, it’s Rex vs. whoever). Turing put in a plea of “guilty,” because he

didn’t think he did anything wrong. He was convicted, and given a choice

between prison or chemical castration. He chose chemical castration (injection

of female hormones for a year), but shortly after, he took his own life by

cyanide poisoning.

Angel got a kick out of this picture of Benedict Cumberbatch. She says he looks like Sherlock. In summer.

|

| Bletchley mansion staircase |

The Library at Bletchley was actually operational during

WWII. They’d stock it full of books for Bletchley workers who wanted to read

during their downtime. For the movie The Imitation Game, they located Commander

Denniston’s office here.

But the real Commander Denniston’s office was here:

I guess they thought the Library was more imposing than this airy, white scrumptious room? I completely fell in love with this room when I entered. I wish it was my room!

As we were staring in awe of this beautiful room, a Bletchley worker came in to pose a question to us—could we tell what the difference was between the passport in the glass display case and the poster passport:

The passport is Commander Denniston’s. He was going to

Poland to meet with the Polish mathematicians who’d broken the Enigma codes

back in 1932.

We noticed that the dates were different--one dated July 28, 1939, the other dated July 19, 1939. The worker said

that to find the answer, we should go on the 12pm tour. We’d been on this tour

already the other day, but the tour pretty much explained everything that we’d

already read in Block B. The worker said, “No, you should really check out this

tour. The Chief Tour Guide will be giving it and it’s very informative.” Angel

and I looked at each other and shrugged, why not? Give it another go—maybe we

can learn something new.

Turns out, the worker was sooo right. I’m so glad he told us

to go (you have to get tickets to reserve your seat for the tour. It’s included

in admission, but they want to make sure each tour is limited in number).

Our tour guide, Robert Lovesey, was extremely funny and

entertaining. He was dressed up in a proper suit (could be because today is

November 11th, Remembrance Day for WWI) and really reminded us of an

older James Bond-type. We were really glad we decided to do the tour again

because this tour was nothing at all like the one we experienced on Saturday.

He added so many interesting tidbits and personal anecdotes about Bletchley –

for example, that his father was a dispatch rider. Many years after the war,

when Bletchley Park was opened up to the public, Robert and his wife decided to

go to Bletchley Park for a day out (similar to what we were doing today). When

he mentioned this to his father, his father exclaimed “Bletchley! You can’t go

there! It’s restricted!”

Another really cute story he told us was one of an elderly

couple who came to Bletchley years ago and during the demonstration of the

reconstructed Bombe machine, the wife (who by then was in a wheelchair) pointed

out that the demonstrator wasn’t running the machine the way the Wrens would’ve

run them back in WWII. This shocked her husband, who exclaimed that he worked

in Hut 6 during the war. After all these years, husband and wife never even

talked to each other about what they did during the war!

Our tour guide paused to make sure everyone had walked over

to the next spot on the tour, and said “Hope I haven’t lost anyone. I shall be

sacked!” We all laughed and one woman said “Oh no, you can’t be sacked – you’re

too good!” He chuckled and said “Now I shall blush.” And when he actually did

blush, “How quaint! Delicious!”

We had passed by the car park on the first day but hadn’t

had time to go in. We made it a point to check it out after the tour, as Robert

told us that one of the cars was used in the WWII movie, Enigma (which Dad

loves). The way he told this to us was: “A lot of the men get a kick out of

knowing that Kate Winslet’s bottom has graced the seat of that car.”

Another interesting tidbit we learned from Robert was that

the stone lines in the grass were the actual outlines of the original huts

which were torn down after the war. They were discovered when the grass was

being restored.

|

| Tower of Station X (so named because it's the 10th radio tower established, not because of the letter 'X') |

Bletchley Park is also known as “Station X” since it was the

10th radio station in Britain. However, to avoid being detected by

the Germans as a point of transmitting radio messages, the radio station in the

tower above was taken down in 1940 and a separate radio station was established

5 miles away.

Bletchley was never the target of a direct bomb attack,

although the stables were hit by a bomb that fell and didn’t detonate. Another

fell next to the canteen. The Germans never knew about Bletchley and what was

going on at the park; the above-mentioned bombs were most likely dropped by

mistake and no one was hurt.

Cottage 3 where Dilly Knox, Alan Turing, a lot of brilliant minds came together to break codes:

Cottage 3 where Dilly Knox, Alan Turing, a lot of brilliant minds came together to break codes:

Robert cheekily mentioned that only one type of code breaker

was allowed in cottage 3 with Dilly Knox. Can you guess? Female! =P

The tennis court Winston Churchill ordered to be installed to help alleviate stress at Bletchley. He’d visited Bletchley and saw some of the BP workers playing a game of rounders. He asked why they weren’t playing tennis, and one of the BP workers said they didn’t have a tennis court. So, Churchill promptly installed a tennis court for them.

Commander Denniston was keen to provide a lot of

entertainment for the young workers at Bletchley (most were 22-30 years of

age). He knew the value of alleviating stress, and boy, was working at

Bletchley stressful. If you missed one letter, the whole code might be off and

you’d have wasted a lot of other people’s time and efforts, so everyone was

keen to concentrate 110% 24/7.

The huts were recently returned to their former states as

part of an 8 million pound restoration project.

Hut 8 is where Alan Turing led his team into breaking

codes. There were at least 3 chess grand masters who’ve worked in this hut. It

was in this hut that codebreakers broke the German naval Enigma ciphers, which

was a major feat, considering the German navy’s codes were more secure than any

other unit. They not only had a revolving codebook, they had 4 Enigma rotators

instead of 3. The achievements of Hut 8 allowed the admiralty to reroute

British ships around U-boats to deliver much-needed supplies to Britain (the

U-boats were sinking every merchant ship they could find in the English Channel

so to cut off Britain’s supplies).

Wowza. I hate these kind of questions. Angel said

they routinely use these types of questions as interview questions at Google.

Guess I’ll never work there. Ha!

In Hut 8 is a tribute to the pigeons of WWII. The pigeons

had a 95% success rate at getting the messages to the proper recipients. No

way! That’s crazy high! Germany knew the importance of pigeons and several

years before WWII broke out, they began establishing secret pigeon lofts in

England to do reconnaissance work. The Brits only figured this out because

someone saw a man carrying a pigeon very secretively onto a train. So they

followed this man off the train and ended up finding out about the German

lofts.

During WWII, anyone found with a British pigeon would be

immediately executed by the Germans.

Hut 3 & 6 were less than 5 feet away from each other.

Hut 6 was run by Gordan Welchman, another brilliant mathematician. He improved

the Bombe’s design.

All around Bletchley are posters warning the workers to not gossip. One middle-aged woman on the tour was talking to the tour guide and she said that during WWII, everyone was taught to not talk about what they were doing in the war effort, to keep things hush-hush in case enemies were listening in. It was a vastly different culture back then. Townspeople knew something was going on at Bletchley—I mean, c’mon, 8000 people commuting in every day to work here. But no one asked, and the townspeople never told the outside world of these massive commutes. It’s very different, especially when you consider nowadays with Facebook and Twitter. Or as Robert put it, “Nowadays with ‘Twitmail’ and the like, people wouldn’t last 30 seconds [without spilling a secret]!”

All around Bletchley are posters warning the workers to not gossip. One middle-aged woman on the tour was talking to the tour guide and she said that during WWII, everyone was taught to not talk about what they were doing in the war effort, to keep things hush-hush in case enemies were listening in. It was a vastly different culture back then. Townspeople knew something was going on at Bletchley—I mean, c’mon, 8000 people commuting in every day to work here. But no one asked, and the townspeople never told the outside world of these massive commutes. It’s very different, especially when you consider nowadays with Facebook and Twitter. Or as Robert put it, “Nowadays with ‘Twitmail’ and the like, people wouldn’t last 30 seconds [without spilling a secret]!”

Angel wants to take our tour guide home. But she’ll settle for a teddy

bear and call him Lovesey. A Bletchley Park bear costs 13.99 pounds, so Angel’s

resolved to go home and make her own…complete with the plaid suspenders that

Porgy, Alan Turing’s teddy bear, wears. Oh, and a red poppy.

Alan Turing’s bear, Porgy:

Alan Turing’s bear, Porgy:

Alan Turing’s mother wrote a book about her son after he

died. She details his childhood, and as I read it, I kept thinking that Baby’s

a lot like Turing.

Indeed, some of the women (2/3 of the staff at Bletchley

during WWII were women) commented that the engineers and mathematicians who worked

here may be geniuses, but they were quirky, eccentric characters. You have John

Cooper, who’s sitting next to the lake bench and all of a sudden, jumps up,

throws his mug into the lake and shouts, “I’ve got it!” He’d just broken a

German enigma code.

You also have Dilly Knox, who would only allow the female

members of his team to go into Cottage 3 with him to break codes. The men had

to do it somewhere else.

There’s two Typex machines in Hut 6:

Hut 6 is where they decoded the Enigma messages. Hut 3,

right beside it, is where they translated and analyzed these decoded messages

to make sense of what the Germans were actually saying.

Whereas the messages of Hut 8 had to be sent to Hut 4 for

analyzing via an armored escort, the messages between Hut 6 and 3 were sent via

a little wooden chute:

Video 2714

Genius.

Hut 11 is where the Bombe machines were kept. WRENS were

enlisted to keep them operational 24/7. They worked in 3 8-hour shifts and what

really sucked is that the 8-hour shifts they worked changed from week to week.

So you might work 8-4 this week, then midnight to 8 the next week. It threw off

the human internal clock and some of the women couldn’t cope with this. The hut

was poorly lit and drafty (my God was it chilly when we went in there! I could

feel icicles forming between my toes!). Coal was rationed, so the fires they

lit were very weak. Imagine standing there from midnight to 8am, trying to

operate the machine in the dead cold of winter! I don’t even think my brain

works below 7 degrees C.

Angel: Here’s Jen playing a WREN. Oh, that rhymes.

Teeheehee.

Jen: Yeah, it’s really hard work. You had to be very fast

linking the letters up to each other, and damn, just trying to cram in the

wires was tough.

Most of the BP workers didn’t have cars because fuel was

rationed. There were a lot of buses of various shapes and sizes transporting

the workers to BP. A lot of them walked, trained in or rode bikes to BP. Alan

Turing was one of many who liked riding his bike to work:

Here’s me listening very attentively to the volunteer

demonstrating how to use the Bombe machine:

Angel: Actually, what the picture fails to show is that the

rest of the audience is standing and listening intently. Jen was standing and

actually took the time out DURING the lecture to walk all the way around the

back of the Bombe to grab a seat. Yeah, real attentive.

By this time, it was already 3pm. The National Computing

Museum is open daily from noon to 4pm, so we needed to get a move on. It’s

situated on Block H that’s part of the BP campus, but rented out by the

National Computing Museum. This is where you go to view the Colossus. The original

ones were dismantled right after the war so that the Russians wouldn’t learn of

Bletchley’s existence (and that the Brits had figured out how to break German

Enigma codes), so the Colossus on display is one that was recreated by a group

of dedicated, passionate engineers. Tony Sale led the effort. He interviewed

postal workers who directed him to salvage yards, and at those salvage yards,

he was able to pick up whole slates of original pieces of the Colossus. Some of

the postal workers were quite crafty. They’d been ordered at the end of WWII to

destroy any papers relating to Colossus’s design. Some kept a few of the

papers, which is why they have been able to use the these to recreate the

Colossus.

Why postal workers, you might ask?

Because during WWII in Britain, the Post Office Research Labs

was a place of total and complete innovation. The post office was responsible

for telephone wires as well as the post, so the research center is where all

these new technologies of how to improve telecommunication speed and such were

being developed.

Max Newman, Alan Turing’s mentor and good friend, had

designed the Heath Robinson, a codebreaking machine that was used to find the

wheel settings of the Lorenz. But it relied on two strips of tape churning at

incredibly high speeds, and the tapes would often break in the middle of a run.

Which meant the run would be rendered useless, wasting valuable time.

Newman got together with Flowers to brainstorm ways to

improve the Robinson. The design Flowers came up with? The Colossus:

The thing is massive. Seriously.

The Bombe that Alan Turing designed was used to codebreak

the Engima, which operated with 3 rotators (4 in the case of the German Navy).

But Hitler and his higher-up generals were using a completely different machine

that stumped BP for a long while. They had no idea what Hitler was using.

Until a German operator typed up a 4000-character long

message to send from Athens to Vienna. Vienna didn’t get the message and asked

for the message to be sent again. Probably irritated by this time (I mean, it does take quite a while to type out 4000

characters on a typewriter), the German operator broke a basic rule of sending

messages: never use the same setting. He didn’t rotate the wheels of the encoding

machine.

So when BP got the intercepted messages and noticed that the

two messages both started with the same 12 string of characters, they knew they

had something very special on their hands. They had depth.

John Tiltman took these two 4000-character messages and went

to work right away. He was the first to break some of the code…manually. He then passed it on to young

William Tutte, and told him to make sense of it.

Bill Tutte didn’t have much faith that he’d be able to break

the code, but wanting to seem busy, kept at it for several weeks. He finally

realized that they were dealing with a machine that used 12 rotators instead of

the 3 that the Engima uses. He was able to design the fundamental architecture

of this mysterious German machine without ever having seen what the real

machine looked like. This achievement of his is called “The greatest

intellectual feat of WWII.”

It wasn’t until almost the end of WWII that the Allies

captured one outside Berlin. For the first time, they were able to see what

they’d been dealing with. The Lorenz SZ42.

The Enigma has 59 million million million possibilities. The

Lorenz SZ42 has 1.6 million billion

possibilities. Yeah.

Using reverse engineering, Max Newman used the information

Bill Tutte had discovered and designed the Heath Robinson to break the Lorenz

code. As you can see from above, the machine wasn’t very reliable because it

broke the tapes.

Newman asked Flowers to take a look at the Robinson to see

how they could improve upon it. Flowers went back home to think and design, and

came back with the mammoth Colossus design. When Flowers showed this to the GC&CS

headquarters, he was denied funding because headquarters thought it would be a

complete waste of time and money. Just look at the darn thing—it looks so

complicated, my head hurts looking at it! I can imagine that must’ve been what

the heads of BP were thinking when Flowers showed them his designs.

One of Flowers’ colleagues said that, “the basic thing about

Flowers is that he didn’t care how many valves he used.” The first Colossus had

1500 valves. The second, 2500 valves. Crickey!

When one of the workers telephoned the Ministry of Supply to

request several more thousand valves (they weren’t allowed to say what the

valves would be used for—Official Secrets Act, remember?), a Ministry official

asked, “What the…hell are you doing with these things, shooting them at the

Jerrys?”

So Flowers went to the Post Office Research Labs where he

worked and he was approved funding there. After Flowers and his team assembled

it at Bletchley (it was too hard to transport otherwise), Flowers gave the

heads of BP a demo. The Colossus went off without a hitch—it broke the Lorenz

relatively fast. There was silence and a noncommittal “We’ll get back to you on

that.”

Flowers had asked them to give him advanced notice if they

required more Colossus to be made, but he didn’t get any answer. Instinctively,

he knew they’d be wanting more of these machines, so he ordered the parts with

lead times in advance. He was right.

In all, 10 Colossus machines were ordered by BP.

The Colossus is considered to be the first electronic

programmable computer in history.

No comments:

Post a Comment